Where do I start? I have never written a play before!!

First, there is no wrong way to write your story. It is your story to tell. But knowing some elements can help you form a script that you will want to come back to over and over!

This guide can be referenced in preparation for our seasonal events or workshops!

What Will Be Covered

Script Structure/Content

Elements of a Plot

Protagonist vs Antagonist

Explicit vs Implicit Writing

SCRIPT STRUCTURE/CONTENT

The core of a play script focuses on two elements: Words and Action. This aligns with what drives a play. Imagine sitting for 90 minutes straight watching a live person blandly talking and barely moving on stage. Personally, I would rather watch paint dry than sit through that. I say this because a good script emphasizes the importance of word placement and movement.

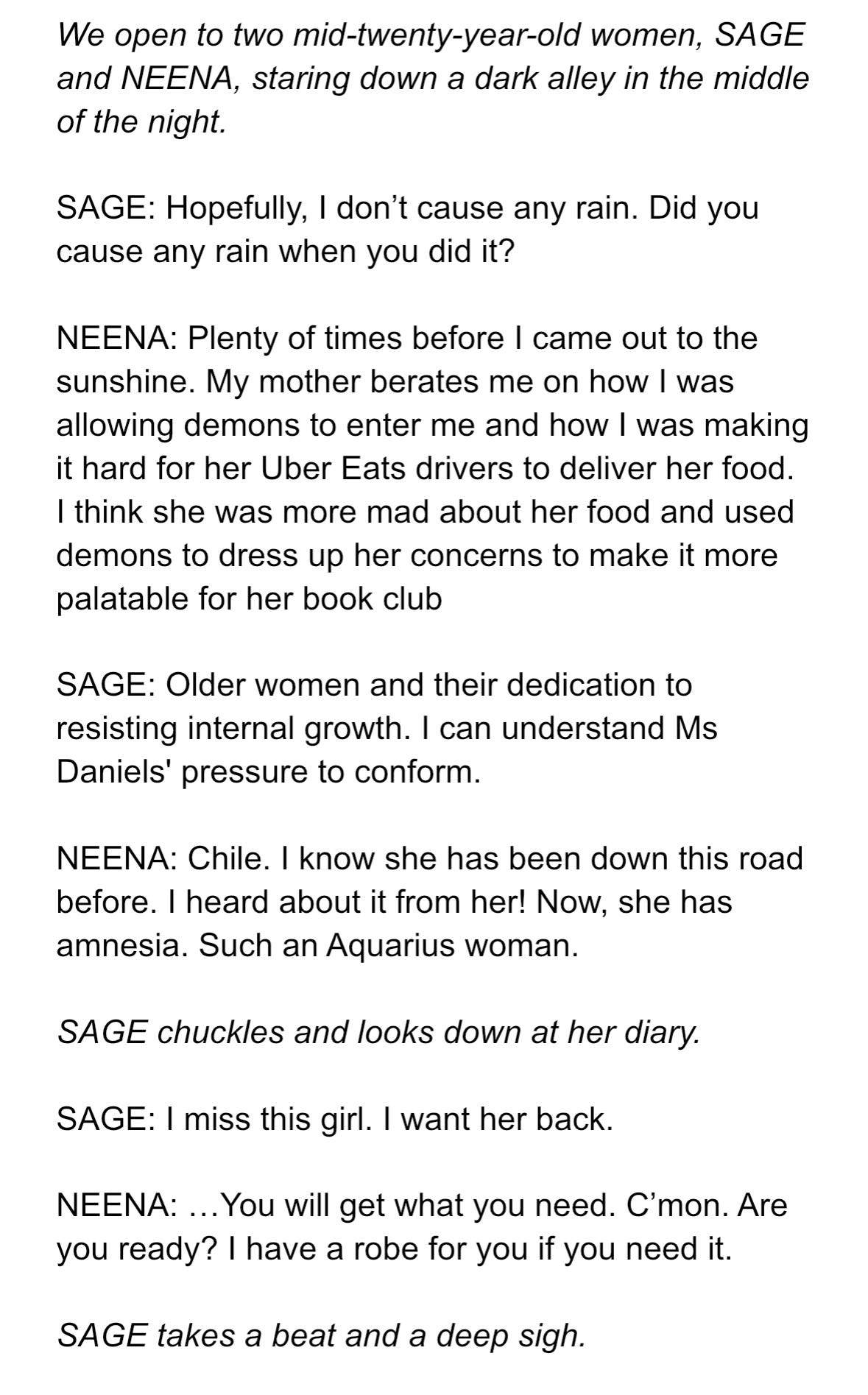

Take a look at this play script below:

The words in italics are the action, while the dialogue has the characters’ names followed by what they say. Pretty simple, right?

Things to keep in mind when writing:

Unless you have a Broadway budget (let’s pretend that we don’t), keep your setting to one or two locations. Personally, focusing on a single strong location adds more impact to your script.

Be as descriptive as you'd like for your action block! Instead of “Lisa is sitting in her house,” say “Lisa is sitting on her bedroom floor holding a Word-Up magazine under low lighting.” This is the perfect space to have fun with your words!

Try only to add actions that help your story. Is Lisa yawning a result of a boring story, a hint towards her affection for someone, or is it just a yawn? If it is the latter, then axe it from your script!

Play with your dialogue! Remember, word choice is a crucial part of delivering a message. Consider the difference between “You make me feel sad” and “You make me feel ashamed.” The word sad is a broad term that includes shame, and choosing shame more effectively guides your story in the direction you want it to go.

Capitalize the character’s name (e.g., NINA) in the action block. This is simply a convention rule.

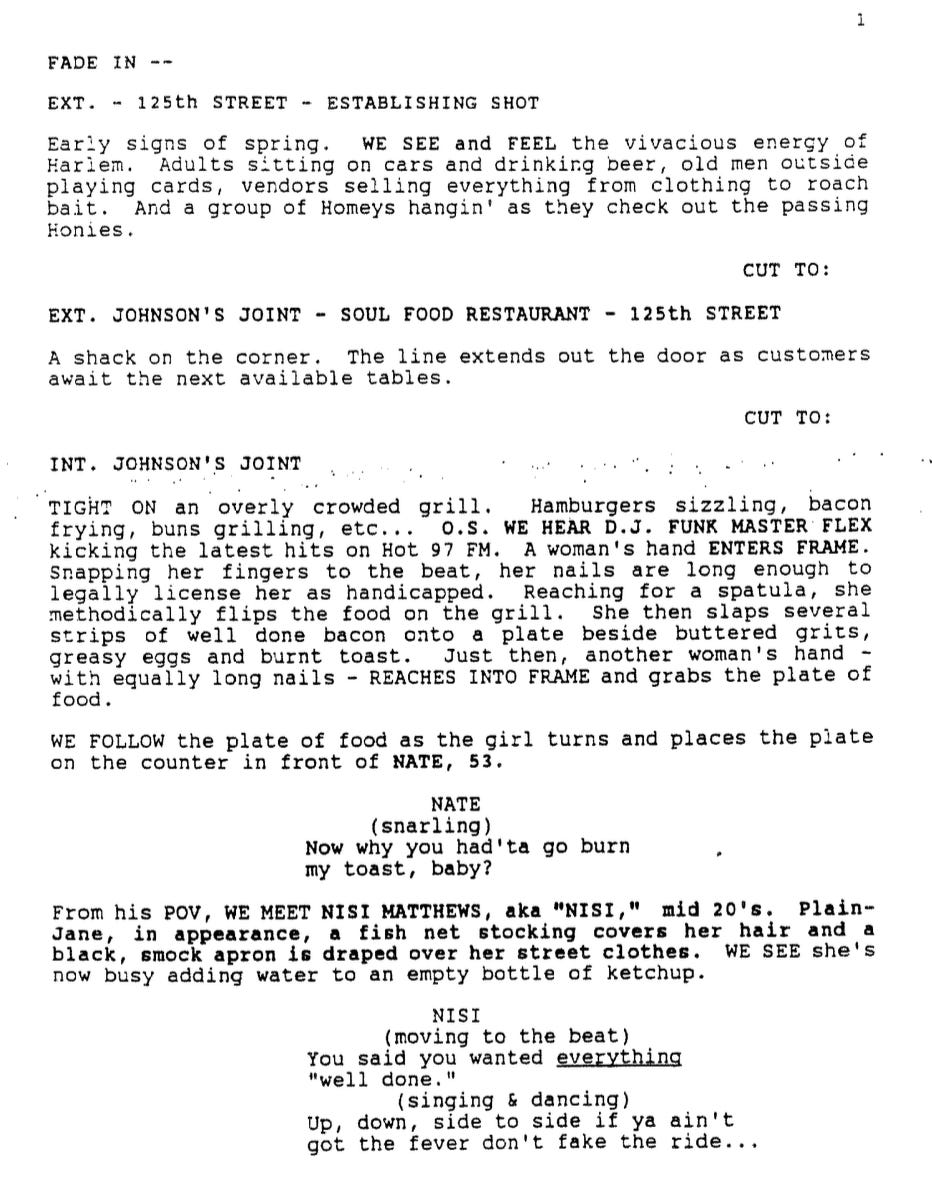

For my film lovers and writers, play scripts are vastly different from film scripts in how they convey their message. Take a look at a sample of this script from 1997 B.A.P.S. below.

Differences Between Film Scripts and Play Scripts:

A film uses many locations to tell a story. The script above had two location changes before the dialogue happened. Film has the luxury of not being live, which allows scene cuts to different places. Plays are live, and location changes (unless masterfully done) can add significant downtime, making a play feel choppy.

An emotion in a film does not solely rely on dialogue. Cut scenes, film shots, music, etc., build on the emotion of a film. This means that film can use less dialogue and place less emphasis on it. Plays use dialogue more heavily as a way to communicate the world of the script.

Screenwriting action blocks are mainly for filming or shot directions, while playwriting action blocks focus on movement and interaction with the environment. For example, the film script will say “CAMERA CUTS TO A GRILL WITH A BURGER BEING FLIPPED,” while a play will say “Denzel begrudgingly gets up from his chair to walk over to the grill to flip the burgers.”

ELEMENTS OF A PLOT

Now that we have a structure, what do you put in the script? How do I not write a scrambled mess in script form?

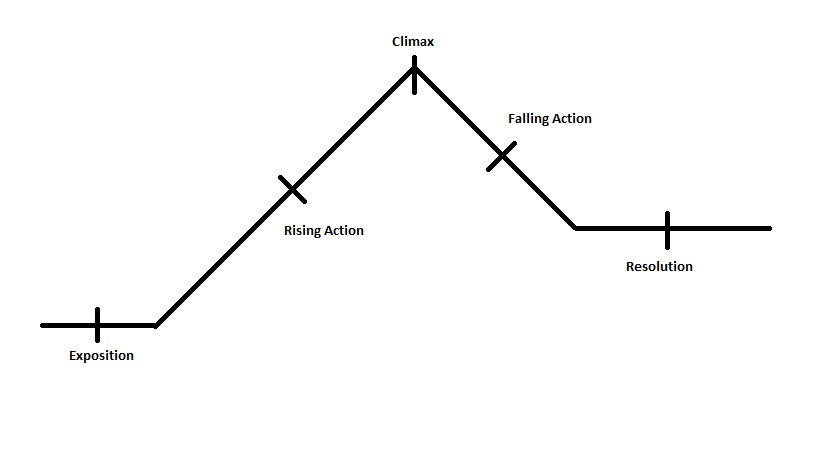

There are a plethora of ways to form a plot, so I doubt that you will create a scrambled mess. However, the easiest format to start with is to use a linear plot structure:

EXPOSITION

INCITING INCIDENT

RISING ACTION

CLIMAX

FALLING ACTION

RESOLUTION

Exposition: The world before the inciting incident. Not present in every story.

Ex: Patsy and Kyle are sitting at the dining table in peace while listening to jazz music.

Inciting Incident: The start of the conflict; The end of the exposition and the beginning of the rising action.

Ex: Kyle’s phone rings with a woman’s contact name that Patsy does not recognize.

Conflict: The central struggle between two opposing forces that is the primary driver of the plot.

Ex: Kyle is a serial cheater to Patsy, which leads her to think that he is cheating again

Rising Action: A collection of events/decisions that creates tension leading up to the climax.

Ex: Patsy questions Kyle about the woman calling him. This leads to an argument between the two, with dishes flying.

Climax: The central part of the story that requires a decision that begins to decrease the tension; the “no turning back” decision.

Ex: Patsy grabs a gun and points it at Kyle, which leads him to lunge at her. At that moment, Patsy pulls the trigger.

Falling Action: The rapid aftermath of the significant decision shows the decrease in tension.

Ex: A bleeding Kyle stumbles backwards and falls on the floor. The argument becomes silent.

Resolution: The aftermath, where the tension from the original conflict has nearly vanished. The beginning of a new world, unlike the world at the beginning.

Ex: Patsy realized that her life had just changed, and she started cleaning up. The lady on the phone turned out to be Kyle’s estranged mother, with whom he had recently reconnected.

This is the basic structure that you will see in different forms of media that you come across!

PROTAGONIST VS ANTAGONIST

Who will be the CHARACTERS?! Character building is a topic that deserves its own post, but we can start by identifying the protagonist and antagonist, especially in a two-character script.

The protagonist is almost always one person or a group representing a single voice (e.g., a corporation/town) that makes a significant decision during the climax. The antagonist opposes the protagonist and is the main force that causes the conflict in the inciting incident.

So, does that make the second character the antagonist? No, not necessarily. The second character can be the antagonist (Protagonist vs. Villain), but they can also be a helpful ally to the protagonist.

Different Types of Antagonists:

Protagonist vs Villain: Batman vs the Joker

Protagonist vs Self: Girl battling with a depressive episode, deciding whether or not to self-sabotage her relationship with her girlfriend.

Protagonist vs Corporation/Group: A woman suing the job she interviewed for due to racial discrimination.

Protagonist vs Nature: A woman stuck in a flash flood and trying not to drown in her car.

For a beginner writer, it's important to focus on creating a short script with two characters to practice writing compelling dialogue. It’s easier to get to know two people at once rather than fifteen. Keep that same mindset when writing, because understanding your characters is key to giving them a strong voice. I will explore this skill in more depth in a different post!

EXPLICIT VS IMPLICIT

We have the script structure, plot elements, and characters — what is left?

Well, let’s touch on the content of the dialogue quickly. What makes a script great is that the audience is allowed space to be detectives to figure out what decision the protagonists will make at the climax. This means that you have to leave open areas for interpretation.

This leads to explicit vs implicit writing:

Explicit: Clear, direct, and unambiguous dialogue that has no room for interpretation

Ex: “Diane, I am mad at you!”

Implicit: Dialogue that conveys meaning indirectly through suggestion, symbolism, and subtext

Ex: “Diane, I am not going to the dinner tonight. I am tired and want to go to bed right now.”

Both example dialogues can convey the same meaning, but the implicit dialogue requires more interpretation to understand that the character is upset, or the audience could read it another way. This makes the experience more interactive and enjoyable. You can lead the audience to a particular direction using extra dialogue and/or actions to frame your story. For example:

DIANE goes upstairs for a while to prepare to leave. When she comes back down to exit, she sees JACOB still sitting and yelling at the TV. She shakes her head and quietly leaves.

Implicit writing not only allows the audience space for interpretation, but it also gives you room to enjoy creating your world. Of course, too much implicit dialogue can leave the audience with too many questions, making it less enjoyable. You need to balance implicit and explicit writing to convey the message you want to leave.

Well... We've reached the end! You should now be able to create masterpieces about your life. I'll explain these elements and more in future posts, but for now, go ahead and write your heart out!